To think of access through the shared table/mat is to think about hospitality as structure; a practice that circulates among hosts and guests alike, where everyone can create conditions of care and attention, not just receive them. Just as the door marks arrival, the table marks relational presence. What would it mean for cultural institutions to host not just visitors but atmospheres of mutual attention? For artists to equally see themselves as host. To make space not only for arrival but for staying – for lingering, for being fed, for being known. In this way, relational access becomes visible; it is the care that extends beyond formal provision – the improvisation, attentiveness and reciprocity that make a room feel warm and inclusive.

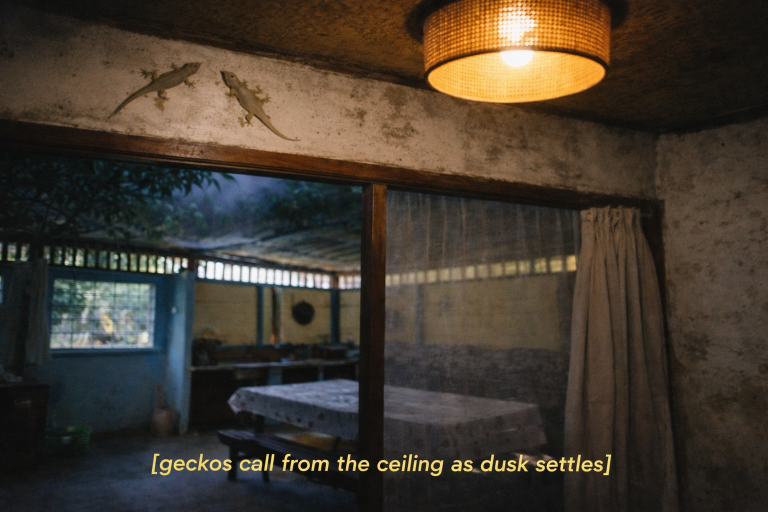

Collaborating with artist Yasmine Aminanda, we ran a workshop titled The Shared Mat, exploring relational access through Southeast Asian practices around food and hosting. The workshop took place in my home in North London with a small group of invited artists, curators and creative practitioners – many of whom were strangers to begin with. Yasmine, who had recently returned from Indonesia, brought a creative ethos of shared practice. Her approach centres on shared gestures and happenings, where thinking happens through doing and conversations spark creative actions.

The workshop began informally. Participants helped themselves to nasi kuning, chicken rendang and pisang goreng, moving through the space at their own pace. Some arrived early and quietly contributed by helping to set up mats and dishes. Others engaged in conversation, while some observed in silence.

Setting the mat

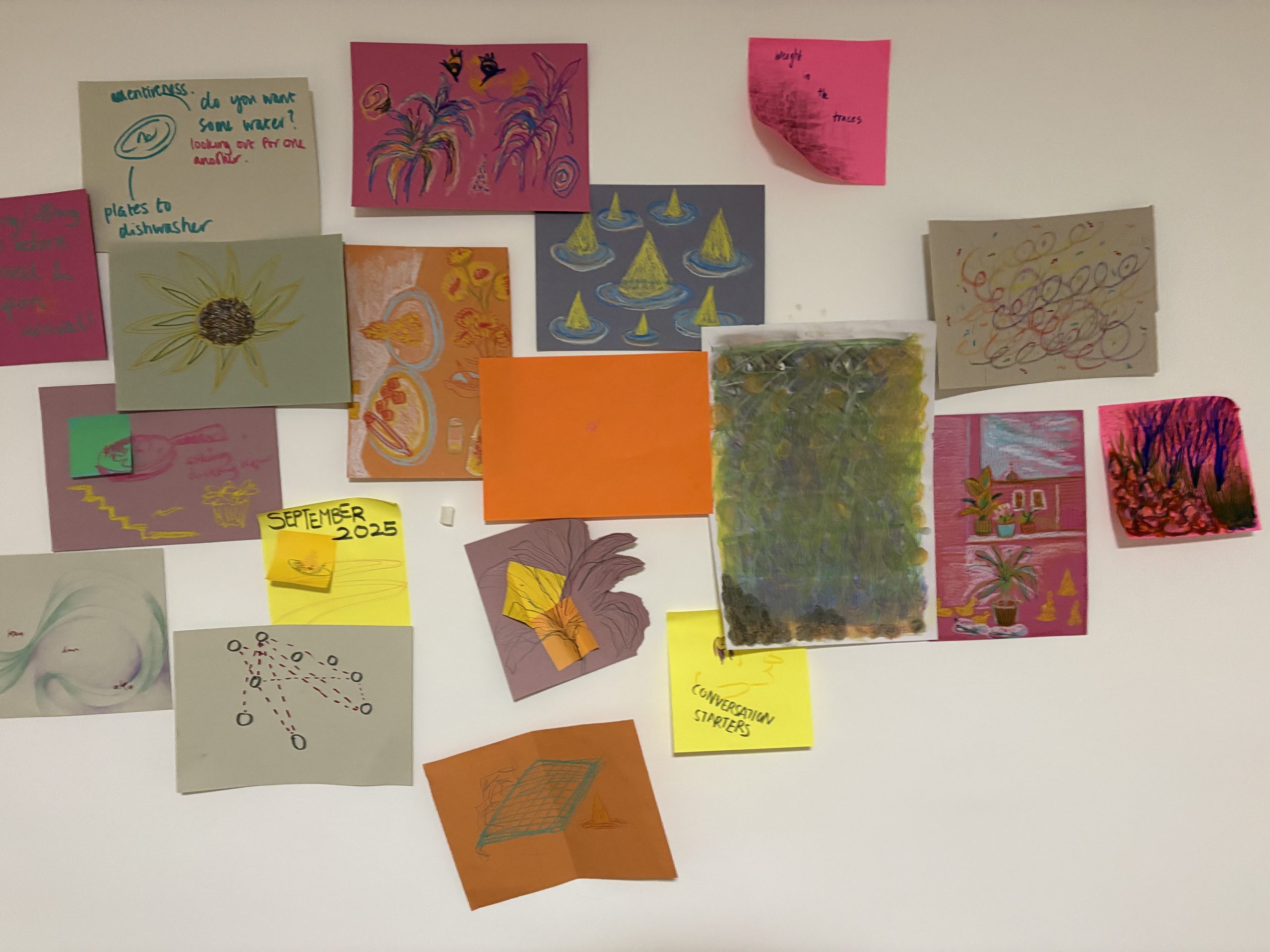

Before the meal, we introduced an icebreaker using words from Southeast Asia which we thought were relevant to relational access – gotong royong (mutual cooperation), bayanihan (helping each other), nongkrong (hanging out and getting to know one another as people), musyawarah (deliberation and consensus) and rukun (social harmony and mutual respect). Participants matched definitions on the wall, sparking conversation about care, collaboration and shared responsibility. The exercise set the tone for the workshop; relational access is something we do together, felt in gestures, attention and negotiation and hospitality is mutual – everyone was both hosting and being hosted in the unfolding space.

As participants arrived, the dynamics of mutual hospitality became clear to me. Some helped set up mats and dishes; others engaged in conversation or observed silently. Each small gesture from passing a dish, offering a seat, attending to another’s comfort, was a meaningful enactment of co-hosting. Hospitality was not one directional; everyone could give and receive care.

During the meal, participants sat on mats with communal food. While elders traditionally eat first in many Southeast Asian cultures, we discussed how this could demonstrate attentiveness and care rather than hierarchy. The meal/shared mat became a live experiment in mutual hospitality, noticing, sharing and negotiating participation without forcing anyone to act in a particular way.

Observing Relational Access in Action

Care circulated quietly but deliberately throughout the workshop. Some participants arrived early, helping in the kitchen, setting the table whilst others passed dishes and cleared plates without being asked. These small gestures reminded us that relational access doesn’t rest on a single person; it emerges when everyone notices and responds to what others need.

Yasmine and I coordinated the day’s activities, preparing the space while checking in with participants. To respect our capacities, we structured planning around short, focused sessions, through texts, shared high level intentions, divided responsibilities and trusted each other to enact them – stepping in to support one another when needed. This approach modeled relational access among collaborators, showing that relational access is not just from hosts to participants but within collaborative relationships themselves.

At the same time, we recognised the risk of overwhelming others with too much care. Balancing attentiveness with respect for autonomy is central to relational access: how do we notice and support without obligating?

How do we create space for contribution while letting people engage in ways that feel right for them?

Optional participation and layered engagement

One lesson I carried forward from Mind the Gap when supporting Alison Lam in her workshop with autistic communities was the white/gold card system – participants flip a gold card when they want to speak and a white card when they prefer not to engage. Facilitators respect the cue and do not probe. Seemingly small, this gesture creates safe space, honours autonomy and reduces pressure to perform participation.

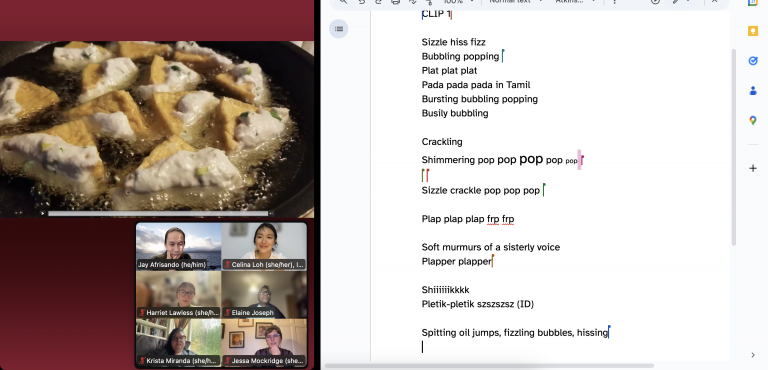

Optional participation doesn’t mean people don’t contribute; it means offering multiple ways to engage while respecting autonomy. In The Shared Mat, we layered participation:

- Some exercises invited discussion aloud.

- Others were reflective or non-verbal.

- Participants could contribute in writing, drawing, or silently, with their work feeding into collective discussion later.

These multiple modes enact mutual hospitality, each participant can host the space for themselves and others in ways that feel comfortable, while the group attends to and receives those contributions.

Reflection & Translation

The Shared Mat shows me that relational access and hospitality are inseparable; care circulates when everyone has the opportunity to host and be hosted. Small gestures, shared labour and attentive observation all contribute to spaces where relational access can emerge. Yet these moments also highlight the tensions and questions that remain.

Even when hospitality is mutual, some participants inevitably carry more embodied labour – setting up, guiding, noticing – while others may not feel able to host themselves fully. How do we ensure that mutual hospitality does not unintentionally privilege certain voices or overburden particular participants? How do we balance attentiveness with respect for autonomy, so care does not become control?

Scaling these practices beyond intimate workshops will be a challenge. Larger institutions, dispersed teams, online collaborations and bureaucratic structures introduce constraints that may limit how hospitality circulates. Cultural practices inspire relational framework but translation across contexts requires sensitivity because what works in one shared space may not map neatly to another.

Finally, relational access resists easy measurement. It is felt rather than formalised, emergent rather than fixed. How can institutions, artists and collaborators sustain environments where everyone can host and be hosted equitably, while navigating the realities of labour, power dynamics and differing capacities?

These are the questions that continue to guide my research. The Shared Mat offered a glimpse of what is possible when care, attention and contribution circulate mutually. But it also reminds me that relational access is always evolving, negotiated and unfinished.

This research by Celina Loh draws on Southeast Asian communal practices such as eating together as a starting point to explore how relational approaches might enrich UK structural access frameworks, fostering togetherness, mutual hospitality and belonging. From this grounding, the work extends into collaborative listening, sound and facilitation practices, aiming to inform more holistic and culturally responsive approaches to inclusion in the UK arts and cultural sector.

Loh’s research is supported by the British Art Network (BAN). BAN is a Subject Specialist Network supported by Tate and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, with additional public funding provided by the National Lottery through Arts Council England.